Too Old for Ibex?

A high-altitude hunt in Kyrgyzstan tests the author’s mettle.

By Jon R. Sundra in Cabela’s Outfitters Journal

Is there a hunter alive who at one time or another on a physically exhausting or miserable-weather hunt hasn’t asked himself: What the hell am I doing here? I think not, not if you’ve done much hunting at all. Me, I’ve done more than my fair share and have therefore found myself asking that question more than once, but never with more seriousness than on a hunt I made last October in Kyrgyzstan for mid-Asian ibex.

I’ve sinced turned 68, and I’m in pretty good physical shape for an old coot. I don’t run marathons or anything like that, but I watch my weight, and I exercise almost daily. But I’ve lived my whole life at less than 600 feet above sea level, so I’m used to air with some body to it.

The Siberian ibex–the mid-Asian being one of several subspecies found in Afghanistan, southern China, India, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, Pakistan and Russia–is a trophy that made my “must-have” list early in my hunting career. I think most hunters have such a list, whether realistic or not, of certain animals they would like to hunt more than others. It’s a purely subjective think. I have had no desire to shoot a bison or musk ox, but I desperately wanted to hunt Rusa stag on the South Pacific island of New Caledonia, sitatunga in the papyrus swamps of Africa and jaguar in the jungles of Central America. Those and a few others I have long since been able to check off my list, so for the past decade, only the ibex remains. I knew it was one of the most physically challenging hunts a man could undertake and had no intention of putting it off as long as I did. It just happened that way.

Preparations

Fast forward to the February 2007 Safari Club International convention in Reno, Nev. Knowing I would turn 67 in June, I decided if I didn’t make the hunt soon, chances were I’d never make it. I booked my ibex hunt for Oct. 5-15, but on one condition: that my booking agent Sergei Shushunov, who heads up Russian Hunting, LLC, accompany me. I didn’t want to make a trip that far and that remote without a companion who spoke Russian.

As it turned out, between the time I booked the hunt in February and my departure on Oct. 5, I managed to coax an old college buddy of mine, Ed Notebaert, to book the hunt. A mere 13 hours in the air from JFK to Istanbul on Turkish Airlines, an additional 5.5 hour flight to Bishkek, the capital of Kyrgyzstan, and 13 hours by car, and “suddenly” I found myself at a modest but comfortable base camp at 9,600 somewhere in the south-central portion of the country.

Mountain Air

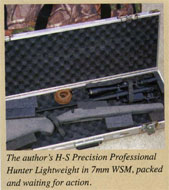

Traveling constantly for nearly 36 hours to a place 10 time zones from home takes a lot out of a person. We were dog tired but managed to stay awake for the remainder of the first day in an effort to acclimate to the altitude. All I know is that after walking 200 yards up a slight incline to where the guides had set up targets for us to check our rifles, I was panting like The Little Engine That Couldn’t. And the next day, we’d be hunting 4,000 feet higher. We were both shooting 7mm WSMs, mine an H-S Precision Professional Hunter Lightweight, and Ed a custom Ruger with an E.R. Shaw barrel.

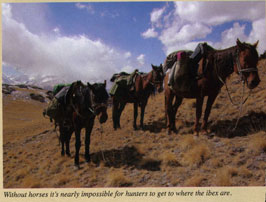

Thank God for horses. At day-break the second morning, Ed and his two guides took off from base camp in one direction, and my two guys, Asan Ali and Danier, and I headed off in another. Danier spoke enough English that it was OK with me for Sergei to stay in camp. After all, Danier had hunted ibex before in this place and surely knew things I didn’t.

It’s hard to describe just how tiring it is for a flatlander to move around at 14,000 feet. Just getting off the horse and climbing a few yards to crest a ridge and glass the breathtaking vistas beyond was exhausting. Constantly on my mind was HAPE, high altitude pulmonary edema, a potentially fatal malady. According to the research I did, at 8,500 about 1 percent are affected; at 14,000 the percentage is much higher. The lack of oxygen affects the heart, and the symptom is the inability to catch one’s breath. The only “cure” is to get down to a lower altitude–fast. Though it took a while after exertion of any kind, I was always able to catch my breath, so Danier said I’d be OK.

Success

I got my ibex in the fading light of that first day. Good that I did, for I don’t think I could have hunted another day, let alone the four more scheduled in fly camps we were to set up wherever we happened to be at dusk. We thought we’d be hunting out of base camp, not in pup tents in the ionosphere in 10-degree weather.

By midafternoon we had seen maybe 30 ibex, but no really good males we could reach before dark. We actually saw more Marco Polo sheep than ibex, but collecting one would have cost an additional 25 grand. It was incredible luck that the ram Asan Ali spotted bedded down about a thousand yards away actually stayed put for the three hours it took us to stalk within shooting distance. I made the shot at a lasered 185 yards–close in terms of ibex distance.

During the final stalk up and down a couple of steep ravines, I thought I was going to spew my lungs out. It was during that time I asked myself the question I posed at the beginning of this story: What the hell am I doing here? When I look at the picture of me and my ibex, however, the question pales to absurdity.